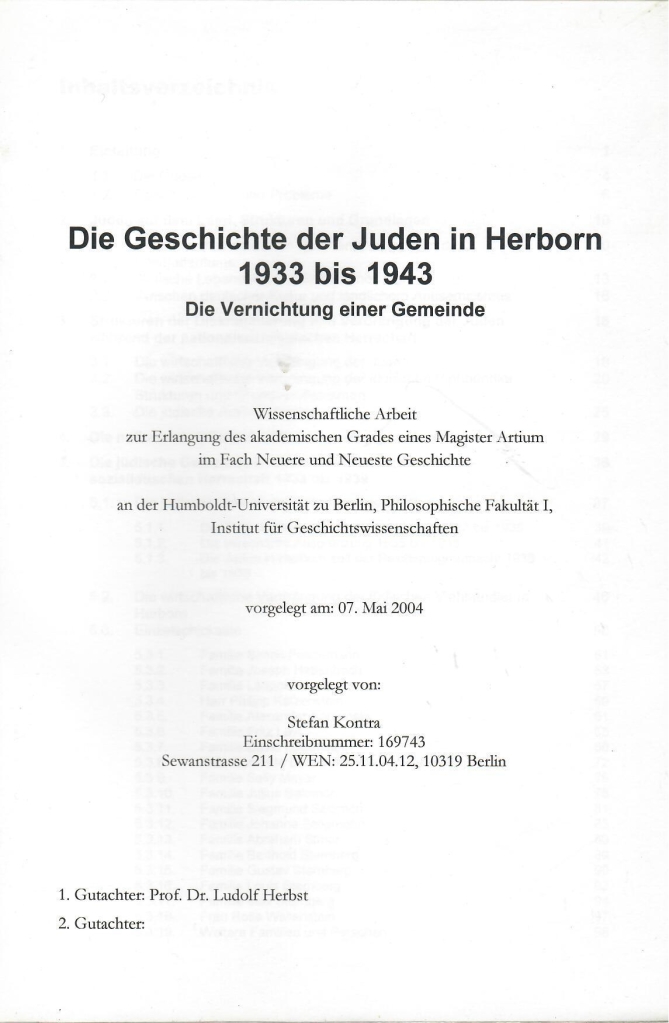

This page cites numerous studies regarding the Jews of Herborn and the surrounding state of Essen. Primarily the source of this page comes from a work titled “The History of the Jews in Herborn from 1933 to 1943: The Annihilation of a Community” written by historian Stefan Kontra.

Another source document, titled “The Persecution, Emigration, and Annihilation of the Herborn Jews” was created by students of the Klaus Kesselgruber School and the Youth Education Project of the Lahn-Dill District and heavily cites Kontra’s report as well as utilizing many of his same sources.

The exhibition attempts to show, with the aid of documents, the sad journey, the expulsion into exile, and the extermination of the Herborn Jews. It makes plain that beginning on November 30, 1933, the Herborn Jews were exposed, step by step, to an increasing discrimination and persecution by public authorities, the Nazi Party, and also their fellow Herborners, which ended finally in expulsion and for many, in death.

Additionally, click here for a brief summary of the Jewish community of Herborn.

For mathematical reference regarding many of the financial statements in this document: one Reichsmark in 1935 has the approximate value of $5.73 in 2020. Conversion tables courtesy of the University of California at Santa Barbara.

The Jewish Community of Herborn up until 1933

The first documented mention that can pin down Jewish life in Herborn dates from the year 1377. This document referred to a house that found itself in the possession of a Christian and was described as a Jewish School (possibly formerly a synagogue). The Herborn Town Archivist, Ruediger Stoerkel, presumes that at this point in time already,

no more Jews lived in Herborn. Presumably they had fallen victims of the big pogrom from 1348-1350, as in Wetzlar. The wave of pogroms spread on the strength of specific rumors that were spread that the Jews had poisoned the wells during the plague epidemic in the middle of the 14 th century and that this caused the illness. Almost all of the Jewish communities, with the exception of a few towns (as well as areas in Austria and Bohemia), were destroyed.

Only 300 years later (1646) did the history of the Jewish community allow itself to be pursued further with the aid of documents and certificates. It is thanks to the various activities of the Herborn History Association and the Town Archivist that it was pretty well investigated: In the year 1646 the sovereign permitted a Jew from Gladenbach to

settle in Herborn. This met with the approval of the Herborn Council which, in the general settlement ban for Jews exempted by the sovereign himself, refers only 1½ decades later, in the year 1660, to the Jews obtaining the right to sell meat retail, showing that by that date Jews were again resident in Herborn. In the years 1680-1840 the synagogue of the Jewish community was situated in the house at 22 Corn Market. There is still today a Jewish bath house, or Mikva, restored or reconstructed there for visiting. The Jewish cemetery was situated between the town wall and the town cemetery until around 1700. From around 1870 the Jewish community buried their dead in the

cemetery in Au, which can still be seen today. Between 1680 and 1840 the Herborn Jewish community never numbered more than 8 households. The small community admittedly was always led by a community leader, usually a rabbi. In 1889 the community had grown to eleven households with 52 members.

When in 1933 the Nazis came to power, Herborn was the home of 92 Jewish townsmen and townswomen.

Most of Herborn’s Jews were poor. Even though several families belonged to the “middle class” e.g. the Hecht, Hattenbach, Sternberg and Seligman families, most ran small businesses. Because of the trade restrictions imposed on them, altogether they had had only narrow livelihood opportunities until Jewish emancipation. The Herborn trade guilds watched jealously over the colonial goods trade so that no Jew could penetrate it and break the monopoly. Several townsmen of Jewish origin belonged to the volunteer organizations. The cattle merchants David Löwenstein, Louis and Berthold Sternberg belonged to the volunteer fire department around the turn of the century. One of the founders of the volunteer fire department was the watchmaker, Aaron Lucas. There was a member named Löwenstein on the Herborn soccer SV in 1920. A document from the Nazi time gives evidence that at least 2 members of the Social Democratic Party were of Jewish origin.

These association memberships of a few Jewish inhabitants was frequently cited as evidence that the Herborn Jews had become integrated into the life [of the community].

Presumably however, they were also exposed, during their centuries of history in Herborn, to antisemitism and hostility toward Jews, for it is undeniable “…the hostility toward Jews was a more or less latent settled component of Western Christian culture and remains strong in remnants still… the Jews were the minority par excellence in the

Christian West.” (Strauss/Kampe Hrsg. Antisemitismus, Bonn 1985, p.15).

Election Results of the last Free Reichstag Elections for Herborn

Reichstag 1932 I Reichstag 1932 II Reichstag 1933 National Socialist German Worker Party 1663 votes 54.9% 1457 votes 48.7% 1854 votes 57.0% Social Democratic Party 637 votes 21.0% 556 votes 18.6% 551 votes 16.9% Communist KPD Party 171 votes 5.6% 247 votes 8.3% 150 votes 4.6%

The People of Herborn elected the National Socialists and their allied parties with a big majority in 1933. That brought to the Jewish population a time of persecution and expulsion from their home.

On April 31, 1933, the NSDAP called for a boycott of Jewish businesses throughout the country. Obviously the NSDAP in Herborn sought to organize the action locally. The boycott was meant by the Nazis to exclude the German Jews from the economy. After that the Nazis left it at that, this one-time unprecedented action, because even they came to realize that an immediate and radical exclusion of Jewish trade must have considerable negative consequences for the whole economy. The displacement of the Jews from the economy, culture and public life was to be begun later in a planned and organized manner. The source material concerning Herborn in the action is very scanty, so that no evidence could be found relevant to how “successful” the boycott was.

After the 4/1/33 action, boycotting continued extensively but quietly, concerning the part played by different areas of the country, either through participation or turning a blind eye. There continued to be open actions from the ranks of the Party.

A document of February 17, 1934 includes that in a summons from the District Council, the cattle dealer, Louis Suesskind makes a complaint on the record.

I know for sure that in all the rural communities of the Dill Region, the local agricultural leader is instructed to openly give out to have no dealings with Jews. The local agricultural leader (…) In Erdbach said to me, himself, that he had an order regarding this in his pocket. Who gave this order, I don’t know. But I am aware that the local agricultural leader (…) announced this order in Erdbach in the school, to the long established townspeople. Such requests were announced in almost all the rural communities of the Dill Region, in several cases even accompanied by the ringing of the town bell.

This process caused the District to direct the mayors of the area, “ to abstain from any future action that can be considered as forbidden economic intervention.” (StAW410/543)

It refers to a decree of 9/1/33 by the State Economics Minister concerning the particularly powerful boycott action against Jews, defined as an inadmissable intrusion into economic life.

Such “unauthorized” measures produced, as early as the action of April 1 itself, negative reactions abroad, to which the authorities were not indifferent. In addition, according to public and Party authorities, the arbitrariness led to negative consequences in the economy (e.g. unemployment due to reverses in Jewish businesses, and foreign

currency problems) which were unacceptable in view of the continuing economic crisis situation. That was what the exemption, to which the Council referred in its decree, was derived from. However that did not mean that now economic discrimination, sanctions and assaults stopped. It was never a “good time” for the Jewish population. Evidence of this are the occurrences from 1936 to 1939.

On December 27, 1936, The Dillenburg District informed District Leader Scheyer that, “Local Councillor Driedmann Mueller from Münchausen…, who had partnered with Jewish businesses on the occasion of the Martini Market in Herborn, must step down as Councillor. This was requested in accordance with #52 paragraph 2 of the German Community Order enacted during the so-called “Direct Connection” [Gleichschaltung] allowing the appointment of a replacement.” (StAW 483/4171 b)

On April 19, 1937, the Commissioner of the NSDAP of the Dillenburg District wrote,

that the Borough Justice… (from) Münchausen had sold a cow to the Jew, Daly Meir, in Herborn some time before, and through the dealership of one Wilhelm Ciliox, Herborn.

I ask you to have the Borough Justice questioned, to whom was the cow sold? If he sold it to the Jew, Meir, the question must be considered, whether he can remain as Borough Justice. But if he sold it to Wilhelm Ciliox, Herborn, Ciliox must be punished as he has no trading permit for that.

Please send me the result of his testimony.

Heil Hitler!

~Scheyer’(StAW 4834171 b)

On January 6, 1939, the District Officer of the NSDAP wrote to the Mademühlen area group that from the customer book of the Jew, Sternberg, confiscated in Herborn during the “Jew action” (i.e. in the course of the November 9, 1938 pogrom) it emerges that, in all, 5 persons from Mademühlen or Münchhausen had done business with Sternberg. The Business Officer continued:

I request that you order and make clear very energetically to the people concerned from the Office of the District Group, the position of National Socialism. If a Party member is found to be named, it is in accordance with Party regulations to take action against him. Should one of them hold an honorable public office, a recall should immediately be executed.

~ (StAW 483/4171a)

Jews and Jewesses who were politically active or of an activist nature were especially suspiciously spied on.

An undated list, probably drawn up around 1935/36 (StAW 483/4206a) reports the Herborn Jews, Martin Levi and Walter Mayer as previous members of the SPD and as “politically unreliable”.

Boycott Order of the NSDAP to the Rank and File

In each local group and subordinate organization of the NSDAP, Action Committees are to be formed immediately for practical detailed planning for carrying out the boycott of Jewish businesses, doctors and law practices.

The Action Committees must popularize the boycott through explanation and propaganda. Principle: No German is to ever buy from a Jew, or allow himself or his subordinates to recommend [Jewish] merchandise. The boycott must be universal. It will be carried out by the whole populace and is designed to strike at Jewry in its most sensitive spot.

The Action Committees must be sent into the smallest farming village, in order to strike the Jewish dealers especially in the flat country. Essentially, always stress that, for us, it is a matter of self-defense measures that we have been forced into.

Moreover, it is necessary as never before that the whole Party stand as one man behind the leadership. National Socialists! Saturday at 10 o’clock the Jews will know who it is with whom they have picked a fight.

The Pogrom of November 9, 1938

The boycott measure and harassment against Jewish fellow townspeople worsened visibly. On November 30, 1938, Jewish lawyers lost their licenses; beginning October 5, internal passports had to be identified with a “J” and on October 28, 17,000 stateless Jews were driven out of Germany over the border into Poland. This action affected the family of Herschel Grynszpan, who, therefore, shot dead a member of the German Embassy in Paris, to protest this injustice. This incident served the Nazis as a welcome reason to carry on the campaign against the Jews consistently and now carry out the pogrom night.

The occurrences during the pogrom of November 8, 1938 – the Nazis called it National Kristallnacht [broken glass night] – are only comprehensible for Herborn with difficulty. The reports are contradictory and the original sources are worse than poor. It is certain that the Synagogue was ravaged. Whether this took place on November 9 or November 10, or from the 10th to the 11th is hard to reconstruct.

“Without one Jew having one hair twisted” wrote the local newspaper. Admittedly, former Herborners, who as Jews survived the Nazi regime, see it very much differently. In the context of a joint project between the Lahn-Dill District Youth Education and a youth group led by the former Herborn curate, Schmidt, in 1988, Elfriede Klater, Fred

Sternberg and Betty Sternberg described in personal letters the events as seen through the eyes of children in Jewish families.

Elfriede Klater wrote:

On that day, I had religious instruction at the Synagogue. On the way there someone said to me, ‘Elfriede go home; the Synagogue is on fire.’ I went home and told my mother, who then forbade me to leave the house. Being a child, I could not understand why. On the same night, the 8 th-9th of November, 1938, the SS and the Gestapo came to us. We were already in bed and I don’t know what time it was. We heard them come up the stairs and immediately knew that the Nazis were coming because we recognized the sound of the boots. It was several of them. They kicked the door open and asked first for my father, but he was in Siegen, to buy there new guts and skins, and wasn’t expected home until at least the next day. When my Grandpa asked what they wanted, they took the old man, with his 80 years, and pushed him into the next room. They said to him, ‘We don’t need you, old Jew.’

Afterwards they beat him up all over. My mother said to them that my father would report to them immediately at the Town Hall as soon as he returned. One of these men lived in Auf der Muhlbach [Mill Stream Street or neighborhood]; I played with his daughter all the time. Maybe other people were there who used to call themselves our friends. It is also possible that my elders told me their names, but I have forgotten them in the meantime and my dear Mother has been dead for 22 years and my dear Father since March 1987.

When my father came back from Siegen on November 9, 1938, he immediately went to the Town Hall. Toward evening my mother sent me to the Town Hall with something to eat. There a man told me that my father wasn’t there anymore, but rather with the other Jews in a train to be transported away….

Betti Sternberg (Ken’s aunt) reported:

… In the so-called National Kristallnacht all the windows in our house were smashed with big stones. My father was taken into so-called protective custody and was locked up for 2 days in the Herborn Town Hall.

From there he was transported to Frankfurt into the armory and then to Buchenwald concentration camp. Thanks be to God, he came home from there, half starved and sick in body and soul. He was only set free because I sent in his decorations and the Iron Cross from the first World War and then only on condition that he would remain in Germany no longer than 3 weeks.”

Already in 1938, state authorities and Nazi organizations acted together closely. The November terror was organized with German thoroughness.

There is evidence that Max Sternberg and Hugo Löwenstein were abducted into a concentration camp. Hugo Löwenstein was only released from the concentration camp on January 18, 1939, and emigrated in April of the same year to England.

The Herborner Tageblatt [daily paper] wrote in its 11/11/38 edition:

Fierce Indignation and Revulsion

The news of the death of the German Envoy First Class, Herm vom Rath, in Paris, has aroused the deepest pain and grief in the German community and in ourselves. It is completely understandable if the fiercest indignation and deepest revulsion against the Jewish assassin Grünspan [sic] and his racial community makes itself noticed. It

hasn’t in the least come to riots, but the excited crowds in the streets of the city coalesced in a threatening manner. In the course of these days the houses of all the Jewish families have been searched for any weapons, without one Jew having one hair twisted.

Kommandantur

bcss. State Concentration Camps Oranienburg,1/18/1939

Sachsenhausen

RELEASE [unable to read the rest due to old typescript]The Jew Hugo Löwenstein Born on 5/8/99

in Herborn was from 11/12/38 to 1/18/1939 put in a concentration camp

The release took place on 1/18/1939

His conduct was

[can’t read]:

He was [something xxx’d out]

to the local police authority of his home District and so forth

[more xxx’d out]

to report The Camp Commander

[Illegible round stamp with eagle] [Illegible signature]

___________________

[SS lightning symbol] Oberführer[Illegible illegible] Oranienburg

~Herborn files

The Pressure to Emigrate Increases

During the following period the pressure on the Jewish community increased. The N-S regime organized their step-by-step exclusion from all societal fields. Citizenship was denied them; the Nuremburg race laws and the prescribed execution of these laws were defined. Whoever is a Jew loses his occupation and source of livelihood; he becomes locked out from the cultural or social life.

Organized state pressure, combined with an open enmity against Jews on the part of an increasing sector of the population, marked their living situation.

Only a few relevent documents referring to Herborn have been preserved. An impression of how the life of the Herborn Jews changed is portrayed in the memories of Elfriede Klater and the Sternberg brother and sister.

Betti Sternberg writes:

The situation of the Jews became worse almost daily. Gradually almost all my friends joined the various Nazi Party groups. They were so indoctrinated against Jews that they would no longer have any contact with me. Once while taking a walk with my parents, I was hit and stepped on by a young man. He screamed at me: ‘You damned Jewish sow, are you still here?’ It was clear to us that we could no longer live in such a country, where so much hatred prevailed and so much injustice was allowed.

Her brother, Fred Sternberg made up his mind, already in 1936, to emigrate. This decision was very difficult for him and his family.

But I had no choice: almost all my Christian school friends and Aryan professional colleagues with whom I had lived in the most perfect harmony for as long as I could remember, would not acknowledge any acquaintance with me and treated me like a leper. I couldn’t bear that

writes Sternberg. An experience that he could never forget portrays the shocking atmosphere against the Jews already in 1936:

In August 1936, before I went away into exile, I happened to meet a former ‘friend’ and schoolfellow in the Bahnhofstrasse [Rail Station St.] in front of St. Leonard’s Tower. When I wanted to say ‘goodbye’ to him, he refused to shake my hand.

By “emigration” we chiefly mean chasing away into exile, which was tied up with the robbery of all the “emigrant”’s assets. Of course, fleeing protected them from physical destruction. Still the price was high which Jews had to pay for life alone. Many had to leave behind friends and relatives who later came into the extermination system. Many would not or could not pay this price; they wanted to remain in their ancestral homeland. Others repeatedly made emigration applications and nevertheless did not escape death.

The kinds of fates that are hidden behind the term “emigration” can be evidenced with the aid of the thousands of emigration documents of the Foreign Currency Authority which are found in the Hesse Government archives in Wiesbaden.

The Family of Simon Friedemann

Simon Friedemann was born on December 4, 1875 in Katzenfurt near Herborn. His wife Karoline, born on May 19, 1878, came from Laasphe. From their marriage they had two children, Erich and Irma. Erich was born on October 18, 1905 in Katzenfurt, Irma was born on December 26, 1907 in Ehringshausen. Both children survived the Holocaust in exile. The parents remained in Germany and became victims of the deportations to the east. Erich Friedemann married on November 30, 1937 and lived with his wife and her parents until emigration on February 10, 1938. Irma married Beni Grünebaum and moved to Düdelsheim. Her daughter Betti was born on April 17, 1934. The Grünebaum family moved to their parents in Herborn in November 1938. In autumn 1939, the daughter and her family were still able to leave Germany.

The family’s economic base was Simon Friedemann’s cattle shop, which he ran on Burger Landstrasse in Herborn. After finishing elementary school in Katzenfurt in 1891, he went to the advanced training school until 1893 and then began training as a horse dealer. He founded his own cattle shop in Ehringshausen in 1905 and ran it – only interrupted by his participation in the First World War from 1914/15 to 1918 – until 1936. His son Erich later went into it:

The company was absolutely good, we had good things to do, we had visited the markets far and wide, we had subordinates and people and we were known in the area and beyond for the sale of horses and cows. It was a respected company with a good value.

Since August 30, 1926, the family was finally based in Herborn and, due to the good behavior, acquired a house plot in the inner city of a house on Kornmarkt 5. Not much information was available on the company’s income. The following profits are shown from the trade tax documents of the city of Herborn from 1927 to 1932: 600 Reichsmarks in 1931 and 240 Reichsmarks in 1932. The magistrate further notes:

From the fact that F. is no longer listed in the tax documents from 1934 (the lists for 1933 are no longer available), it can be seen that he already ceased trading at the end of 1932 or in 1933. According to the consistent statements of some Herborner citizens, it is not true that F. had employed foreign workers in his business. Only his son Erich worked in the business, which was operated only in a very modest amount …

In this case – as is so often the case – there is a statement against a statement. However, it seems certain that the annual income in normal times must have been more than 600 Reichsmarks if the family was able to buy a house and also maintain the business property in the Burger Landstasse.

For the assets of Simon Friedemann there is a list of July 10, 1939 in the foreign exchange file, in which the total assets of 912 Reichsmarks and 150 Reichsmarks are stated. In the list of assets in form Dev. VI 3 No. 2 of March 5, 1940, the total assets consisted only of 599 Reichsmarks. The rest of the property was used up by 1941 and on May 23, 1941 Simon Friedemann asked the foreign exchange office “S” to open the secured account, “… since I have almost no assets left, the continued existence of this account is pointless. I now receive monthly RM from the Reich Association of Jews in Germany Berzirksstelle Frankfurt, 50 Reichsmarks support”.

In the middle of 1941 the Friedemann family had no wealth. The proverbial expropriation of the property shows how quickly the nation robbed families like the Friedemanns. For the 3-story house at Kornmarkt 5, Simon Friedemann effectively received 800 Reichsmarks. The purchase contract was concluded on December 12, 1938 between the Friedemann couple and the R. couple. From the purchase price, which was only 35,000 Reichsmarks, a mortgage of 2500 Goldmarks was paid, so that in the end only 800 Reichsmarks were paid out.

The Friedemann family was assured that they were allowed to stay in the house until their emigration was approved, but on September 18, 1939 they were forcibly expelled from the house at Kornmarkt 5 and had to leave some furniture there. The city assigned them a small apartment at Chaldäergasse 11, which they lived in until their deportation on August 28, 1942.

The Hattenbach Family

Joseph Hattenbach, born on May 19, 1877 in Hoof near Kassel, owned a large country product store in Hombergstrasse in the Bahnhofsviertel district of Frankfurt. He lived with his wife, Rosa, born on June 15, 1883 in Volkmarsen, and with his two children Fritz and Grete in a large apartment building at Dillstrasse 15, which he acquired in 1923

The Jewish fellow citizens Hattenbach and Seligmann did the same [trade]. Hattenbach, a tall, heavy man with thick horn-rimmed glasses at the time, always saluted on all sides.

The Hattenbachs were regarded as respected businesspeople in Herborn, whose country products dealings were of considerable size. Joseph Hattenbach also built a large modern warehouse on Hombergstrasse, in 1926. His son Fritz, born on December 23, 1908, later helped in the fatherly business. Fritz left Germany at the end of 1935 and had to start a new life in South Africa. He later expressed bitterly about the circumstances of his emigration:

As a result of the forced emigration – which at least saved my bare life – my existence, which was rooted in my father’s business, was also lost. As is known, all Jewish emigrants were only allowed to take the princely sum of 10 Reichsmark over the border. Due to my reputation, which had not been compromised until then, the police administration authorized me to take another 50 Reichsmark, which fact was noted in my passport. These six thousand German Reichspfennige (pennies) represent everything I took from Germany.

Joseph’s daughter Margarethe, born on May 17, 1912, trained as a kindergarten teacher in the neighboring town of Wetzlar until 1933. After the Nazi seizure of power, she was unable to find a job. She later immigrated to Belgium and married there on October 18, 1938.

Fritz stated that the annual income from the business amounted to around 10,000 to 20,000 Reichsmarks. In contrast, the city of Herborn only speaks of a “small to medium-sized business”, the commercial income is given as follows.

Year Trade Income 1930 4,350.00 RM 1931 2,880.00 RM 1932 2,200.00 RM 1933 unknown 1934 0.00 RM 1935 0.00 RM

According to information from the city in the same letter, the business was also discontinued in 1935. This coincides with the other sources. The business also no longer appears in the Dillkreis population register from 1938 and the remark “Pensioner” is added to the Hattenbach entry. The shop also no longer appears in the so-called “Directory of Jewish Companies” from August 1938. It can be assumed that Joseph Hattenbach later lived from his saved fortune. The commercial income stated by the city appears to be of little significance if one does not take the years of the economic crisis into account. The IHK Dillenburg estimated the average annual income before 1933 to be about 6,000 to 8,000 Reichsmarks.

The Hattenbach family also placed a departure request from Herborn. When Joseph Hattenbach gave up his business, he had a total of 47261 Reichsmarks, which he later stated to the foreign exchange office “S”. The family gave all their assets, 45,608.00 Reichsmarks , to the Foreign Currency Authority on October 5, 1938. (StAW JS 728) This consisted of their home, the warehouse with stock and a plot of land, as well as outstanding business debts and (probably) also the business bank account, but only small savings book amounts as well as a little cash. Also the FCA issued a protection order over their possessions. The bank and savings accounted for only 2958 Reichsmarks. When the Hattenbach couple were murdered, the Reich Treasury still confiscated securities worth 17,537.50 Reichsmarks and 1020 Reichsmarks from bank accounts.

Writing on October 12, 1938, Joseph Hattenbach asked permission to send to his daughter, staying in Brussels on a study visit, her trousseau consisting of underwear and used furniture. (StAW JS 728) This occurrence makes vivid in how degrading a manner the regulations of the FCA intervened in the lives of the people.

On March 30, 1939 Hattenbach wrote to the FCA requesting a note

By which I am authorized 8,900.00 Reichsmark to pay the Jewish transfer of assets to the Finance Bureau of Dillenburg.

~(StAW JS 728)

“The Jewish transfer of assets” refers to a decree by the government in the followup to the November pogrom of 1938, stating that a billion Reichsmark were to be squeezed out of the German Jewish community. The Hattenbach family were no longer allowed to withdraw the smallest amounts by themselves. On 10/9/1940 Joseph Hattenbach wrote to the FCA:

Mrs. Emma Hirschland, Brussels, my wife’s aunt, asks me to disperse RM 5.50 to the police headquarters in Frankfurt am Main for a copy of a Certificate of Good Conduct for her grandson, Alfred Herz, who is interned. The document is necessary for his emigration overseas. Mrs. Hirschland has lived for some time in Brussels and has very little money. I’m asking to be granted the specified small amount to pay to the above-mentioned place.

~(StAW JS 728)

When the war broke out, living conditions for the parents in Herborn and for Margarethe in Brussels became worse. Margarethe has a 10 month old child, but her husband has been interned as a German citizen since the outbreak of the war. She is almost destitute. Joseph Hattenbach asks permission to transfer RM 600.00 to her account to help with her support. (StAW JS 728)

Here the trace of the family is lost. It is only known that Joseph and Rosa Hattenbach were taken from Herborn to Frankfurt am Main on August 28, 1942 to the Wholesale Grocer’s Market ‘collection point’. According to information from the Nassau Savings Bank, the remaining credit was withdrawn from the family account in the amount of 1020 Reichsmarks in favor of the German Reich and the securities account was released on September 10 and 11, 1942. Rosa Hattenbach was murdered in Theresienstadt on September 20, 1942.

On October 10, 1942 the Hattenbach file was closed with the standard written form:

Order (based on the Gestapo lists of evacuated Jews)

Subj.: assets of Jews evacuated to the East

and the entire remaining assets were confiscated for the aid of the German state. (StAW 728) Near the end of the war, on February 14, 1944, Joseph Hattenbach was killed in a mass murdering of Jews imprisoned at Theresienstadt. The eventual fate of Margarethe and her family is not known.

The Hecht Family

Very little source material has been preserved about Leopold Hecht and his wife Selma. This is not least due to the fact that the couple remained childless and there were therefore no family members who could have emigrated and who could have applied for compensation after the war. This leaves only the foreign exchange file about the Hecht family, which can provide a glimpse of information about the fate of Leopold and Selma Hecht.

Leopold Hecht was born on November 15, 1862 in Rennerod. His wife Selma, born on December 31, 1876 in Frankfurt am Main, was 14 years younger than him. Leopold Hecht was one of the most respected citizens of Herborn and had owned a men’s clothing store in a central location on Hauptstrasse 80 since 1896. You could regularly read his advertisements in the Herborner Tageblatt (local paper) – especially on the big annual markets such as the Martinimarkt (German market festival). A congratulatory article in the Herborner Tageblatt dated November 14, 1932 shows the high reputation Leopold Hecht enjoyed in Herborn:

Merchant Leopold Hecht turns 70 tomorrow, Tuesday. We would also like to congratulate Mr. Hecht on the good health and happiness he will enjoy on his birthday. The business he founded in 1896 has led to the satisfaction of his entire clientele to this day. Mr. Hecht comes from Rennerod and has been living in Herborn for more than 40 years. He has made a lot of friends here through a straight and sincere manner, which is paired with real physicality, and he is enjoying great esteem in all circles. Mr. Hecht is the cultural leader of the Israelite community for 33 years and he belongs to the relief committee for 13 years. May his beneficial effects last for many more years.

Leopold Hecht remained the leader of the Jewish community in Herborn until its end. The extent to which Leopold was integrated into the urban community is not only reflected in the capacity as cultural leader of the Israelite community, but especially in his membership in the relief committee. The relief committee was particularly involved during the World Economic Church for the needy of the city. In addition to this involvement in the community, another memorable side of Leopold Hecht is expressed in Walter Schwann’s memories:

Leopold Hecht owned a textile shop in the current Beckfeld estate. As far as I know, his business was continued by the S. family [unknown which S. family he refers to]. At the Hecht household, we got “Matzen” on every occasion as children. Frau Hecht had prepared for this and was taking precautions. Leopold has been rumored to have a lot of female customers, that has never been proven. [?]

However that may have been! It becomes clear that Leopold Hecht’s business went well. With the seizure of power by the Nazis, this changed fundamentally. There is no advertisement for his business in the newspaper; now the Herborner Tageblatt completely refrains from even mentioning the existence of the business. Unfortunately, the tax documents in Herborn were destroyed in Herborn after the flood disaster in 1984, so that it is no longer possible to reconstruct the income from the business. But you can get an impression by comparing the store with Max Sternberg’s clothing store. Both shops – located in the same branch – were in a convenient location on the main street and both shops advertised on the large side in the Herborner Tageblatt. If you leave the rental income at Max Sternberg disregarded, you get an annual income of around 6000 Reichsmarks. Leopold Hecht’s income is likely to have been similar.

The business no longer existed at the latest in 1938. For reasons of age, it’s like Leopold had given up the manufactured goods store. In any case, it does not appear in the “Directory of Jewish Enterprises” in Herborn on August 23, 1938. However, Leopold Hecht is still listed as a merchant in the Dillkreis population register for 1938, whereas no business is mentioned in the business directory.

Not much is known about the Hecht’s final fate. They had no real property, and they had probably rented the apartment and the business premises at Hauptstrasse 80. While Leopold Hecht seems to have been spared the concentration camp detention after the Reichspogrom, not much else can be gathered from the foreign exchange file. On February 16, 1939, a provisional security order was left. The couple’s liquid assets amounted to 2,700 Reichsmarks and about 7,000 Reichsmarks in securities. In August 1940 there were only 380 Reichsmarks left of the liquid assets and the monthly allowance was reduced from 500 Reichsmarks to 400. In September 1942, after the deportation of the Hecht family on August 28, 1942, the rest of the property was confiscated by the Nazis.

After their deportation to Theresienstadt in August 1942, Leopold and his sister Lina (now Lina Rosenbaum) were murdered on September 19, 1942. Leopold’s wife, Selma, was taken to Treblinka, where all record of her ends.

Mr. Philipp Katzenstein

Philipp Katzenstein belongs to the group of Jewish residents who only moved to Herborn after the November pogrom. Folks like Philipp probably believed they could better protect themselves from the riots in other communities or were safer in a small country town, or they might have relatives in Herborn where they could find accommodation until emigration.

The latter was the case with Philipp Katzenstein when he arrived in Herborn on November 25, 1938 – coming from Volkmarsen. His daughter Rosa, born on June 15, 1883, had married to the Hattenbach family in Herborn and had made a living there with her husband. Now the 91-year-old Philipp Katzenstein found a home in the house of the Hattenbach couple. From there he planned to emigrate to the USA – together with his son Paul, who lived in Münster in Westphalia, as evidenced by a letter to the foreign exchange office “S” dated January 16, 1939:

I intend to emigrate at the end of February or in the month of March with my son Paul Israel Katzenstein from Münster in Westphalia to Little Fells in North America. I need 1000 Reichsmark to prepare this project and also to make a living for the time being…

But nothing came of the emigration plans, only his son managed to escape from Germany with the help of his father. Phillipp Katzenstein’s foreign exchange file documents how the Nazi authorities harassed a 91-year-old man and robbed him of his fortune. In May, Phillip Katzenstein found a place in the Jewish old people’s home in Bad Nauheim and on May 31, 1939 he left Herborn for Bad Nauheim. Two days earlier he wrote to the foreign exchange agency “S”:

… I am in my 91st year and go to the Jewish retirement home on June 1st. I therefore ask you to approve the following. Remaining amounts for my invoice to the Dresdner Bank Bad Nauheim will be transferred to a free account. All of my children have already emigrated. The last one, my son-in-law, is also shortly leaving. Since I then no longer have any requests to release my small fortune, it is necessary that the above small fortune be transferred to a free account. I will then contest my livelihood from this account as needed.

In December 1939 Philipp Katzenstein died in the Jewish retirement home in Bad Nauheim.

Over the years Philipp Katzenstein achieved modest prosperity in Herborn. Even before the Reich pogrom, he agreed with the city administration of Volkmarsen on August 30, 1938, for a purchase price of 9,200 Reichsmarks for his house plot in Volkmarsen. Excluding this amount from the house sale, he does not seem to have had any other bank deposits. However, there are two more letters of approval from the senior president (State Department of Culture) in Kassel in Philipp’s foreign exchange file: the town of Volksmarsen bought an arable land-hold valued at 380 Reichsmarks, and the married couple ‘S’ bought a garden plot for 1020.60 Reichsmark, approved by the town of Volksmarsen. Philipp Katzenstein’s total assets can therefore be assumed to be at least 10,600.60 Reichsmark.

He paid about 2,000 Reichsmark for the so-called Jewish property tax. He also transferred 2,000 Reichsmarks to his son in Münster as a share of the house’s purchase price. For the emigration projects, the foreign exchange office provided him with a total of 2,491.25 Reichsmarks, with which his son Paul used to emigrate his family.

When Philipp Katzenstein moved to the Jewish retirement home in Bad Nauheim in June 1939, he still had around 3,500 Reichsmarks left. On June 4, 1940, son-in-law Joseph Hattenbach wrote to the foreign exchange office “S”:

I send you the papers regarding the security arrangement for my father-in-law Philipp Israel Katzenstein back again. The man died at the age of 91 in December 1939. His last place of residence was in Bad Nauheim & I received the same documents from the Darmstadt foreign exchange office for the same purpose a long time ago. I also informed the Darmstadt office that Mr. Philipp Israel Katzenstein died in December & then the foreign exchange office reclaimed the forms. The latest tax return and income paperwork was submitted to the tax office of Friedberg / Hessen. The fortune is still a few thousand marks.

The Family of Alexander Korsunsky

The history of the Korsunsky family is unique for Herborn in that Alexander Korsunsky was the only immigrant from Eastern Europe after the First World War. He was born on November 20, 1894 in Tszigirin in Ukraine. He took part in the First World War on the Russian side and in doing so he was taken prisoner by the Germans. In the war prison in Wetzlar, in the Herborn area, he met his later wife Dorothea, last name Kreger. Because they lived in “mixed marriage” – according to Nazi terminology – Alexander Korsunsky was no less exposed to the persecution of the Nazis, but most likely this would protect him from being deported to the East.

On July 14, 1920, they married and moved to Herborn. As a trained watchmaker, he founded a watch and jewelry store in Herborn. In the years of the Weimar Republic, he must have run a good business because it was possible for him to rent a shop in Hauptstrasse 58 soon – in the best business location. The recordings of Walter Schwahn – a Social Democratic Party supporter during the Weimar years and a member of the “Reichsbanner Black-Red-Gold” [a political organization seeking to legitimize the Republic government] – also show that Korsunsky was well integrated into Herborn society:

Franz Korsunsky (the “short fifteen”) was a watch and goldware dealer in the later house of the Thomas family next to the Cafe Orania. He counted himself among a clique that made a lot of talk about itself in the twenties with its pranks. He is said to have carted a load of gold and crystal goods into the Berkenhoff house after a phone call, but nobody knows what happened next…

In 1932 Alexander received German citizenship, which the Nazis were soon to withdraw. Since the Nazis came to power in 1933, Alexander lived more or less off of the sale of his warehouse. However, the business only came to a halt in 1938. In the foreign exchange file there is a letter from August 3, 1938 by the graduate in business Friedrich Würz, in which it says succinctly:

After checking the documents and receipts presented to me by Mr. Korsunsky, Herborn, I can declare that all of the above obligations have been settled by payment on August 3, 1938. The liquidation of the company Alexander Korsunsky, Herborn has ended.

The business only existed formally in the handicraft role, as evidenced by a list from November 28, 1938. In the summer of 1938, however, it was no longer included in the “Directory of Jewish Enterprises” in Herborn, and Alexander and Dorothea Korsunsky began plans to emigrate in August 1938. On November 1, 1938, however, Alexander Korsunsky was among those arrested and taken to the Buchenwald concentration camp. There he was released on December 3, 1938, on condition that he leave Germany by January 31, 1939 at the latest. Therefore, with the help of the St. Rafael Club, he tried to emigrate to Brazil via Holland. On February 1, 1939, he reached Holland, where the occupying German Wehrmacht again exposed him to the Nazis in 1940. Emigration had now become impossible and as a Jew living in intermarriage, Alexander Korsunsky began suffering a number of forced labor camps in Holland:

After the capitulation of Holland, the German police took me to the Horn penitentiary on the Zuiderzee. From there I came to the Westerburg-Trene camp. On July 13, 1942, I was released with the obligation to move to another apartment in Amsterdam that was assigned to me, to accept no employment and to be in the apartment constantly between 8:00PM and 6:00 in the morning. On April 5th, 1943 I was arrested again and taken to the Westerburg camp. Because of illness from pneumonia I was released from here again on July 14th, 1945, but I was obliged to sterilize and return to work after restoring my health. I was able to avoid the sterilization with cunning. After my recovery, I was occupied with heavy, unfamiliar work as an earth-worker and dock-worker until I was taken to the Grote-Kehen [Havelte] camp on the North Sea in early 1944, where I was employed by bunkers and fortifications. From there I came to a RAD [Reich Labor Service, an organization employing poor Germans and forced-laborers] camp after the ice front at Zuiderzee and was busy building the airfield. Because I was almost ruined by the heavy, unfamiliar, physical work – but did not want to break completely just before the end of the war – I made the decision to flee and to hide until the end of the war. On October 13th, 1945 I managed to escape from the Havelte camp and I was able to hide under the wrong name until the arrival of the Allies, I lived under the name Nodrod in Amsterdam.

His wife Dorothea moved to Wiesbaden while her husband emigrated to Holland and worked there as a housekeeper. The Gestapo arrested and interrogated her several times. Due to the physical and mental agony she was unable to work after the war and lived in Herborn for a short time.

There are two sources of income from the business: Alexander Korsunsky states his monthly income before 1933 at around 350 to 400 Reichsmarks. The city council of Herborn wrote the following information on January 8, 1952 to the compensation authority:

Year Trade tax on income 1930 1,450.00 RM 1930 840.00 RM 1931 not assessed 1932 not assessed 1933 2,143.00 RM

However, the city made further interesting statements about the business of Alexander Korsunsky, which reveals much of the city’s attitude towards Nazism:

Mr. Korsunski was so fair to take the boycott on his own and relocated his shop in favor of the house owner, in whose house he stayed with his consent until he emigrated from Germany, to a less inexpensive and respectable shop, which first had to be restored through great effort and his own resources. The extent to which the boycott against Jewish shops and craftsmen affected Korsunski’s existence and income cannot be determined by the local authorities due to a lack of documentation …

Alexander Korsunsky confirms this information from his point of view:

At the instigation of the NSDAP, at the end of 1935 I had to exchange my conveniently located shop in Herborn for a shop that was less suitable for my circumstances. In 1937, because I was forced to liquidate, I had to give up this shop and – in order for my wife to live, and our other obligations, rent payments, etc. -I was forced sell my shop and workshop equipment at bargain prices.

The inventory decreased by about 30 percent, the inventory of tools and inventory by as much as 75 percent. Expressed in absolute terms, the assets decreased by 3,096.30 Reichsmarks, which corresponds to an annual loss of 1,032.10 Reichsmarks and meant a monthly loss of assets of 86 Reichsmarks.

The Korsunskys had been trying to emigrate since mid-August and intended to emigrate to South America via Holland. The wife Dorothea therefore sold the home furnishings, which consisted of a kitchen, living room and bedroom, for a total of 800 Reichsmarks. A list of the goods to be moved was also submitted to the foreign exchange office “S” in Frankfurt am Main, with the request that they be given permission to take them with them. After paying a “Jewish emigration tax” of 300 Reichsmarks, the Korsunsky couple could have emigrated. But with the Kristallnacht in November 1938 everything changed.

The Family of Fritz Levi

Fritz Levi lived in Herborn since his birth on February 18, 1905. He lived in an apartment at Oranienstrasse 3 with his wife Selma, maiden name Hirsch, and ran a feed and country products store. Their son Josef Levi was born on May 20, 1933 and their daughter Charlotte on April 24, 1933. Next door to Fritz was his father Meier Levi, born on October 28, 1872 in Katzenfurt, with his wife Berta, maiden name Dannheisser, in Oranienstrasse 3. They were probably also running the feed and country products store listed on Dillstrasse until at least August 1938.

The family had social democratic traditions. Father Meier Levi was integrated into the Herborner Society and was a member of the city council from 1924 and 1926 to 1929. Fritz Levi’s brother Martin was also one of the SPD members, especially since he was classified as “politically unreliable” in a list that was probably created [by Nazis] in 1935 or 1936. Martin Levi left Herborn relatively early, in 1938 he did not appear in any of the population statistics.

No documents have survived about the business, so any statements about the assets and size of the business are impossible. In the compensation file for Fritz Levi there are general statements that the business went “very well” until 1933 and that an annual income of at least 10,000 Reichsmarks had been achieved. No conclusions can be drawn from this information about the business or the assets. There is also no further information in foreign exchange files 4082/39 and JS 4633.

In 1939 there is an indication that Fritz Levi was employed as an auxiliary worker until shortly before his emigration, which means that the business must have been liquidated after the 1938 pogrom. On August 15, 1939, Fritz Levi was removed as “emigrated” from the statistics of the “Movement of Jewish Residents in the Herborn Community”. In his foreign exchange file 4082/39 there is a precise list of his moving goods, which consisted of 2 suitcases of luggage and a handbag.

Fritz’s children came to England on a children’s transport in May 1939. His wife stayed behind and was transported on June 10, 1942. The last years after the departure of her husband and children, Selma lived with her mother-in-law Berta Levi together with the Hattenbachs in Oranienstrasse 3. By selling her furniture, she was able to earn a few hundred Reichsmarks for living, which were deposited in a blocked account with the Nassau Savings Bank. Meier Levi moved penniless to Frankfurt am Main on November 2, 1940, leaving his wife and daughter-in-law behind. It is only possible to speculate about the reasons for leaving Herborn. Most likely, like many other Jews in the rural communities, he also believed that his family could emigrate better from Frankfurt. According to the property declaration on the security order dated July 31, 1940, his property consisted of only 120 Reichsmarks. On August 6, 1940, the foreign exchange office “S” relieved him of the obligation to open a limited security account. On September 15, 1942, Meier Levi shared the fate of his wife and was deported from Frankfurt am Main to Theresienstadt.

The Löwenstein Family

David and Rosa Löwenstein lived in Herborn since the 19th century. Born on September 25, 1866 in Langendernbach, the son of the cattle dealer Jakob Löwenstein and Bette Strauss, David Löwenstein became a prestigious cattle and horse dealer in Herborn. His wife Rosa was born in Weyer on November 24, 1868. The family had three children. The eldest daughter Betty, born on July 12, 1896 in Herborn, married into the Stern family based in Montabaur in the Westerwald. Her husband Willy Stern ran a good business there and owned a piece of land in Bahnhofstrasse 24. The son Hugo Löwenstein, born on May 8, 1899 in Herborn, later made a career as a decorator – among other roles – in the prestigious Louis Lehr department store. Daughter Herta, born on June 21, 1910, later worked as a seller. Both Hugo and Herta are the only survivors of the family, alongside their nephew Alfred Stern.

The Löwensteins owned a 2 1/2-story house in Hainstrasse 13, later named “Street of the SA (Sturmabteilung)”, of 1.86 ares; this included garden lots totaling 2.78 ares. From there, David Löwenstein must also have run his cattle business. According to the Herborn City Council, the business was “a small business”,

… the aforementioned is not listed in the trade tax leverage lists for the years from 1932. It seems questionable whether the testator, at 70, was still able to carry out the cattle trade himself. At least it must be assumed that he has not been able to operate the trade to the fullest in recent years.

The business is only considered to have been registered in 1932, however, that does not necessarily mean that it did not exist before–especially since the tax-raising lists of the municipality did not refer to hiking trades, which was typically the case for cattle dealers. Nevertheless, from the fact that David Löwenstein was still active in the cattle business at almost 70 years of age, one gets the impression that the living conditions were rather modest.

There are other indications for this. According to information from the Nassau Savings Bank, the property had been burdened on December 22, 1926 with a loan of 3,000/2,790 kg fine gold. In addition – according to the land register entry – a mortgage of 5,000 gold marks in favor of a Berlin banker Jacob Frank was taken up on September 30, 1935 on the property. In addition, a security mortgage of 3,000 Reichsmark was dated January 27, 1929.

Nothing has survived from the business documents, only a statement by the daughter Herta Löwenstein, who stated to the compensation agency that the annual income was estimated to be 3,000 Reichsmarks before the National Socialists seized power.

According to foreign exchange file JS 5762, David and Rosa Löwenstein state their assets at 13,000 Reichsmarks, the value of their property. However, 9,000 Reichsmark debts still go away, which are not detailed on the form. In the last few years after the cattle trading business ceased, the Löwensteins were practically supported by their son-in-law Willy Stern, who fled from Montabaur to Herborn with his wife after the Nazi pogrom night and a subsequent stay in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Except for the house lot, the Löwensteins were penniless. Nevertheless, the property was not auctioned off, but became the property Nazi government after the deportation of the Löwensteins. The district economic consultant Fritz Fischer brought a buyer for the house on the day before the deportation of the Löwensteins on August 28, 1942. There was nothing to prevent the sale of the house:

Since the 1st of August 1942, the State Police Department of Frankfurt am Main has confiscated the entire domestic assets of the Jews evacuated on September 1st, 1942. The administration will be transferred to the tax office, so that in my opinion the Löwenstein house can be sold to the buyer Schill you have proposed. In any case, I have no objections to selling the house at its fixed price.

The house ultimately remained in the hands of the Reich and the German Reich collected the rent for three apartments.

The business must have been liquidated by the autumn of 1938 at the latest; it appears in the list of Jewish businesses of the district administrator from August 23, 1938. Herta Löwenstein remembers that the business was systematically expelled from the cattle markets around 1936/1937 and no later than 1937 no more commercial licenses were distributed to Jews.

None of the children entered their father’s cattle business. Daughter Betty married to Willy Stern in Montabaur. The son, Hugo Löwenstein, trained as a window decorator in Erfort. After the First World War, he worked as a touring decorator in the Herborn area and finally found employment in the renowned department store Louis Lehr in Herborn in 1926. He was able to work there until 1935, after which he found a job with Bros. Hermann in Siegen. Hugo lost this position with his imprisonment on November 9, 1938 after Kristallnacht. He was imprisoned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp until January 18, 1939. According to his own information, Hugeo Löwenstein had the following income until 1939:

Year Income 1930 1,920.00 RM 1931 1,920.00 RM 1932 2,100.00 RM 1933 2,100.00 RM 1934 2,100.00 RM 1935 2,100.00 RM 1936 2,400.00 RM 1937 2,400.00 RM 1938 2,000.00 RM (until November) 1939 no income

The figures show that his monthly income rose from 160 Reichsmarks in 1930 to 200 Reichsmarks by 1932. With this income plus a few additional incomes from investments, he made a living. A testimony of a former Herborn neighbor describes Hugo’s return from Sachsenhausen:

… I know Mr. Hugo Löwenstein, who lived in Herborn, very well, and I still know, as I do today, that Mr. Hugo Löwenstein came back in January 1939 after being in the concentration camp for about two months. He arrived so early in the morning that I was still in bed. When he rang the bell, I opened the corridor door and was very shocked to see him.

The dismissal certificate from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp is in the Herborner file, as are the twice-weekly reports to the local police department. Current reports go until April 4, 1939; on April 8, 1939 Hugo Löwenstein left Herborn forever.

Hugo Löwenstein’s older sister Betty married Willy Stern, a Montabaur-based dealer in leather and artisan supplies. The company has existed since 1900 and, according to the Koblenz Chamber of Commerce, the basic trade tax amounts fluctuated around 14 Reichsmarks. The Chamber of Commerce estimated the annual turnover at 30,000 Reichsmarks and the income at about 4,000 to 5,000 Reichsmarks. From the documents of the city of Montabaur, the following trade tax amounts paid could also be determined:

Year Trade tax based on income Trade tax by capital 1930 37.50 RM 18.20 RM 1931 40.32 RM 18.20 RM 1932 15.00 RM 18.20 RM 1933 20.10 RM 18.20 RM 1934 35.40 RM 18.20 RM 1935 15.00 RM 18.20 RM 1936 23.10 RM 18.20 RM 1937 39.00 RM 18.20 RM 1938 31.50 RM 18.20 RM

Commercial income up to 1,200 Reichsmarks and commercial capital up to 3,000 Reichsmarks remained tax-free. For the years 1937 and 1938 it must probably be assumed that the business capital had already decreased so far that it was exempt from tax.

After the Reichspogromnacht and the destruction of the family’s home furnishings by the SA, Willy Stern was taken to the Buchenwald concentration camp. His wife was forced to sell the business and residential building at Banhofstrasse 24. Then she had to leave Montabaur “under a certain pressure”.

The loss of wealth of the couple can be reconstructed on the basis of the account statements that have been preserved since 1938/1939. From this it can be seen that three installments towards the Jewish property levy – with a total of 4,050 Reichsmark – were demonstrably paid, furthermore, according to the letter, the Nassau Savings Bank also paid a check for 1,350 Reichsmark as the fifth installment of the Jewish property levy on November 16, 1939. In the account statements there is also an amount of 1314 Reichsmarks which was most likely debited as the 3rd installment on May 14, 1939. This results in the following list:

Installment date Amount December 30, 1938 1,000.00 RM February 16, 1939 1,700.00 RM May 14, 1939 1,314.00 RM August 16, 1939 1,350.00 RM November 16, 1939 1,350.00 RM Sum 6,714.00 RM

This only affects the payment of the so-called Jewish property tax. From it can be calculated that the Sterns must have had this a total fortune of about 33,570 Reichsmarks in 1938. In addition to the compulsory levies, the income from the sales can also be reconstructed using the account statements. The foreign exchange file JS 9473/3 shows, among other things, that Willy Stern was still able to collect 1,002.55 Reichsmarks in foreign currency in January 1939, of which 950 Reichsmarks went to his blocked account. Likewise, 3,223.50 Reichsmarks and 1,860.90 Reichsmarks were transferred by the Hessen Nassau Life Insurance as surrender values for two life insurance policies. In a separate letter to the foreign exchange office “S” dated June 20, 1939, all sales made are listed, which are compared with the account statement for Willy Stern’s account.

Description Retail price Bank Deposit Statement Outstandings, January 1939 1,002.00 RM 200 RM + 300 RM + 450 RM on account Outstandings, February 1939 159.00 RM Outstandings, March 1939 594.00 RM Outstandings, April 1939 115.00 RM Outstandings, May 1939 248.00 RM Outstandings, June 1939 123.00 RM Sale of warehouse 1,658.00 RM 1,658.04 RM on account Life insurance 5,084.00 RM 5,084.04 RM on account Sale of furniture 927.00 RM 927.60 RM on account Sale of house 1,200.00 RM 13,006.32 RM on account

The outstanding amounts cannot be directly proven in the account statements because the amounts have been paid into the accounts in several parts and some parts have been mostly deducted as tax, making identification very difficult. When the security order for Willy Stern’s account was issued, there was a balance of 658 Reichsmark on it. On March 18, 1940 – after the sale of all assets, mind you – there were 16,560.54 Reichsmarks in the account. After the deportation of the Stern couple, 15,548 Reichsmarks and a further amount of 819.64 Reichsmarks were confiscated.

If one adds the compulsory taxes – and considers the money needed for subsistence of the Stern family and the Löwenstein family – to the confiscated property, one obtains only an outline of the extent that Willy Stern and his wife were robbed by the Nazis until they were murdered.

Since February 1939, the monthly allowance had been increased by the foreign exchange office to 500 Reichsmarks–for January 1939 it was only 200 Reichsmarks. From March 1940 there were only 300 Reichsmarks left. For the year 1939: 5,000 Reichsmarks of withdrawals can be proven; for 1940: 1,900 Reichsmarks; for 1941: 2,100 Reichsmarks and for 1942: 1,400 Reichsmarks, since April only 250 Reichsmarks have been allowed as allowances. A total of 10,400 Reichsmarks were used by both families for a living in the years 1939 until their deportation in June 1942.

Except for the outside receivables, the family has had no income since 1939. If one adds up the compulsory levies, the confiscated final amount when the account was closed, and the probable maintenance costs, the result is an amount of 33,481.64 Reichsmarks, which was withdrawn from the family by being forced out of work, by compulsory levies and, finally, by robbery. This is congruent with the calculations based on the Jewish property tax. On March 3, 1942, as European Jews were being overtly murdered by the Nazis, Willy Stern had to report all expenses to the foreign exchange office “S”.

Henriette Lucas and the Rosenberg Family

Henriette Lucas was born on April 26, 1862 in Herborn to Aaron Lucas. Her father was a watchmaker, a respected member of the community, and was later a founding member of the volunteer fire department. With her sister Johanna Lucas, she ran a textile business in Hauptstrasse 72. However, her sister must have died before the seizure of power, because in 1933 only Henriette Lucas was in the register of residents. There is also an advertisement in the Dillkreis 1928/1929 population register. Walter Schwahn wrote about the two:

The Lucas sisters owned a hat shop in the middle main street. Two inconspicuous, old ladies who couldn’t do anything. [Henriette’s] written notice on the door that her father had fallen for the emperor and the empire in the First World War could not protect her.

With the increasing age of the siblings the management of the business became more and more difficult for Henriette Lucas, after all she was more than 60 years old in the years of the Weimar Republic. Her nephew Alfred Rosenberg, born on July 2, 1907 in Grenzhausen, took over the management of the business. He moved into the house of Henriette Lucas with his wife Berta. Over the next few years, two daughters, Johanna in 1934 and Mirjam in 1938, were born.

After the Nazi takeover – according to Alfred Rosenberg – the boycott had a lasting impact on sales. Alfred’s wife earned something from tailoring for Jewish private customers and Alfred also had a certain extra income from outside orders as a hiking decorator. The business’s turnover was soon no longer sufficient for a living. The business, still registered in the name of Johanna Lucas, still existed in August 1938, but after the November pogrom this too – like all Jewish businesses – was liquidated. Alfred Rosenberg came with the other male Herborner Jews to the Buchenwald concentration camp and remained there until December 17, 1938.

Now the Rosenbergs were trying to get out of Germany. The daughters escaped to England on two children’s transports in the summer. Alfred arrived in Great Britain on August 6, 1939. Berta Rosenberg stayed behind and took care of the old aunt. Berta Rosenberg was deported on June 10, 1942, and 80-year-old Henriette Lucas shared her fate in the second wave of deportations on August 28, 1942.

There are only fragments of information relating to the family’s wealth. Henriette Lucas’ annual income from the profit of the business is said to have been about 2,000 Reichsmarks. The trade tax revenues assessed from 1927 have been handed down:

Year Business Tax 1927 56.65 RM 1928 36.20 RM 1929 37.00 RM 1930 39.82 RM 1931 27.50 RM 1932 27.50 RM 1933 unknown 1934 25.50 RM 1935 25.50 RM 1936 7.75 RM 1937 15.00 RM

These figures show the decline in sales and the loss of income, particularly since the Nuremburg Laws of 1936, which dramatically increased the boycotting of trade and traffic with Jews in rural areas. From 1938 Henriette leased the shop to W.D. [unknown, potentially initials of a fellow resident] from Herborn, who acquired the property in late 1939. It is clear from the foreign exchange file that, apart from the property, Henriette had no other assets. In the property declaration of February 1940, she states her credit at 5,137.35 Reichsmarks. She had already sold the house at Hauptstrasse 72. The total purchase price was 7,879.46 Reichsmarks. She gave the cost of living at 120 Reichsmarks, with the share of rent (stated at 80 Reichsmarks) making up the majority after moving to Oranienstrasse 3. The transfer of 299.65 Reichsmarks to the tax office in Dillenburg coincides with the sale of the house, the exact purpose of which is unknown. At the end of 1942, 3,060.97 Reichsmarks remained from the 5,137.35 Reichsmarks listed in 1940, all of which were confiscated from the German Reich after the deportation of Henriette Lucas. This means that an average of 67 Reichsmarks per month was used to make a living, which was still far below the estimated 120 Reichsmark cost of living. According to Alfred Rosenberg, she also paid around 5,000 Reichsmarks Jewish property tax and Reich flight tax, which are said to have been paid for by securities. However, since the account at the Nassau Savings Bank was only set up as a secured account when the house was sold, information from before 1940 is missing.

With Alfred Rosenberg, the documents are even scarcer. In 1929, after a three-month course as a window decorator in Cologne, he joined aunt Henriette’s fashion business. According to his own information, he earned about 400 Reichsmarks per month, while his aunt earned about 167 Reichsmarks per month as the owner of the business. In addition, depending on the orders, 100 to 200 Reichsmarks from the window decorator hiking trade should have been added, so that the monthly earnings should have been around 500 Reichsmarks. A salary of 400 Reichsmarks seems to have been extremely high for the local conditions in those years, so Alfred Rosenberg’s legal representative made the following clear:

Before 1933 – the exact date can be seen from the files – [Alfred] followed a request from his elderly aunt Henriette Lukas to enter her textile goods retail store in Herborn, Hauptstrasse – to run the business and take it over in the foreseeable future. He lived in a household with his aunt and, as a chosen business successor, did not receive a salary, but rather compensation based on the business income.

This sounds plausible when you consider that Henriette Lucas, unmarried and childless, regarded him as the future heir to the business and that she herself did not use that much money. Nevertheless, when Afred Rosenberg reached England in August 1939, he had 10 Reichsmarks with him, which represented his entire fortune.

The Family of Sally Mayer

Sally Mayer, born on June 24, 1880 in Katzenfurt – and his wife Berta, maiden name Joseph, born on August 30, 1885 – lived at Augustastrasse 19. On June 20, 1912, Julius, the first son, was born in Katzenfurt; on February 17, 1914, the second son Walter followed. Between 1924 and 1925 they built a two-story house with an associated stable in the courtyard. In addition to the plot of land with a size of 2.41 ares (0.06 acres), a garden plot was added that was approximately 2.07 (0.05 acres) ares in size.

The family has been in Herborn since 1925 at the latest. A statement by Heinz Sternberg, a friend of the Mayers, shows that they had previously lived in a rented apartment on Hauptstrasse:

I still remember very well their previous apartment on Hauptstrasse and later in my own home: the Mayers initially had a very large living room with two large kitchen buffets, painted white with a black base. The fact that there were two may be attributed to the fact that Mrs. Mayer still ran a strictly ritual household and therefore needed all the dishes twice.

In 1927 a barn with room for approx. 20 heads of cattle and additional floors for animal feed was added. The older son, Julius, studied chemistry at the University of Giessen after the National Front seized power in Switzerland. He finished his studies in April 1937 at the University of Zurich and never returned to Germany. The other son, Walter, ran a manufactured goods store at Augustastrasse 19. This business was only founded after 1933, because in 1933 it was still missing from the city’s register of residents, but appears in the register of residents from 1938.

There are contradictory statements about the family’s income, which led to a legal dispute between the sons Walter and Julius Mayer and the compensation authority after the end of the Second World War. The two sons, who themselves did not work in their father’s business, stated the monthly income before 1933 at around 1,000 Reichsmarks, on the basis that around 30 to 35 cattle were transacted per month. Contradicting this is the statement made by the city council of Herborn on May 7, 1958, which found in its documents only a reference to a low commercial income. According to the register of business registrations, Sally Mayer had registered a “trade in cattle of all kinds, hides and raw meat” on January 1, 1931. For the years 1931 and 1932 documents were found which indicate the trade tax paid in 1931 at 49.72 Reichsmarks and in 1932 at 22.50 Reichsmarks. For 1936, a 25 Reichsmark trade tax was levied. In principle, the trade income would have to be calculated from the trade tax paid. Most likely, however, this information was only a partial trade, especially since the cattle trade was traditionally operated as a traveling trade and was therefore taxed differently. Now there are two competing interpretations in the sources: First, the paid tax amounts given by the city result in a monthly income of 150 Reichsmarks for 1931 and 75 Reichsmarks for 1932. Such an income could not finance both the upkeep of the family home and Julius’ upkeep in Switzerland. According to another conversion of the trade tax, there is a trade income of about 5000 Reichsmarks, which were also confirmed by the hearing of other witnesses in Herborn. The monthly income can therefore be assumed to be around 400 Reichsmarks a month.

All original business documents or documents about the income situation are missing, so only indirect indications for a comparatively high income can be given. This is supported by the new construction of the residential and business building in Augustastrasse, as well as the construction of modern stables for 20 large livestock. In addition, the good education that Sally Mayer gave his son Julius is also included. Concrete figures on wealth can only be found from 1935 onwards. In the foreign exchange records 1684/38, two lists of assets have been preserved, one as of January 1, 1935, the second shows the status prior to emigration on December 12, 1938.

Statement of assets 1/1/1935 12/12/1938 Operation capital 2,973.00 RM 2,050.00 RM cash balance 300.00 RM goldware (2 watches) Land assets 13,000.00 RM Other assets 1,000 RM loan to Walter 2,413.00 RM liquid. of business 62.50 RM Imperial bond 15,000.00 RM sale of land assets 300.00 RM goldware (2 watches) 80.00 RM Real estate loan 7,000.00 RM Mortgage 560.00 RM Friedemann guarantee[?] 2,711.00 RM Dego levy 1029.00 RM Payment to Willi Meckel Debts / Deductions 7,000.00 RM Mortgage 2,446.00 RM Payment to Kuehne & Nagel Co., Hamburg, for lift and freight 560.00 RM Friedemann guarantee 1,250.00 RM Ship ticket Heumann & Schurrmann, Hamburg 447.00 RM Maintenance Total capital 9,775.50 RM 2,050.00 RM

The sale of the property includes an extract from the sales contract between Sally Mayer and the buyer Wilhelm Schaefer dated June 24, 1937–Sally Mayer’s birthday. The purchase price was 15,000 Reichsmarks. Most of it, besides paying bills, was used for emigration. A total of 7,436 Reichsmarks, from the Dego levy to freight costs and tickets, were spent on emigration. The bill to Willi Meckel relates to new purchases that were intended for emigration. 2,711 Reichsmarks had to be paid to the gold discount bank for these new acquisitions.

After the November pogrom, Sally Mayer – like many other Jewish men of Herborn – was sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp as a so-called “action Jew”, with no information available about the time spent in prison, but he was probably back at the latest in early January because his emigration was imminent.

The family was released on 10 January 1939, but the emigration initially failed because Paraguay revoked their immigration permit, and the two sons, who were already in Argentina, had to apply for a new visa in Buenos Aires. The Mayer family had been registered in Cologne since May 11, 1939, and it was not until December 1939 – after the war had started – that they emigrated via Switzerland and Italy. They were only allowed to take 10 Reichsmarks with them across the border. They also had to leave all of their emigration goods, except for hand luggage, in Germany.

The Family of Julius Salomon

Julius Salomon was born on February 26, 1899 in Werdorf, in the immediate vicinity of Herborn. By profession he was a dealer, like most Jews in the rural regions of Hesse. On November 15, 1933, the family had twin children, Lothar and Silvia. Julius lived with his wife Meta and his two children on Austrasse 12, together with his in-laws Moritz and Julchen Stern. The piece of land itself formerly belonged to Heinrich Sternberg, a well-known cattle dealer and butcher, who sold it to the Salomons before his emigration in 1936. In addition to the actual two-story house, this property also included stables.

There is hardly any information about Julius Salomon’s business. Nothing has survived from the business documents. The only information on this can be obtained from Lothar Salomon’s compensation file. It contains affidavits from former business partners and neighbors in Herborn, which put the annual income before 1933 at 9,000 to 10,000 RM. In one of these affidavits, the income is even estimated at 12,000 to 15,000 RM. The city of Herborn, on the other hand, provides information that Julius Salomon’s cattle trade was registered as a traveling trade and ran until 1938. The income was – according to the master butcher L.S. [?] – annually at about 5,000 to 6,000 RM. Another document comes from the Dillenburg Chamber of Commerce and Industry dated April 27, 1960, which “… contacted the person in charge of the local situation, who informed us that the achievement of an annual profit of 10,000 RM in the years from 1930 to 1933 must be described as possible …”

There is also no information about the assets. All business documents have been lost and the Rhein-Main-Bank, with which Julius Salomon had an account, can only provide information on the past few years. Statements on the assets of the Salomon family can be found in the foreign exchange file JS 7876, which begins with the security order of February 17, 1939. In the form to the foreign exchange office “S” in Frankfurt am Main from February 13, 1940, an amount of 10,840.80 RM is stated by Julius Salomon as bank assets. The amount is not surprising, however, when one considers that the proceeds from the sale of the house on August 1, 1939 are already included.

Only from the amount of the contributions to the so-called “Jewish property levy” can indirect conclusions be drawn about the income situation and the wealth of the Salomon family. Already in the letter from the customs investigative office on the security order dated February 17, 1939, all assets, such as land and property holdings, are recorded. According to Julius Salomon’s letter to the foreign exchange office “S” he had to pay 3,600 RM Jewish property tax to the tax office in Dillenburg. The amount of the Jewish property levy was based on the total wealth as a percentage, so that with a paid 3,706 RM one can assume at least 18,350 RM total assets.

Until his arrest after the Reichspogromnacht and the deportation to the Buchenwald concentration camp, there was no question of the Salomon family emigrating. Lothar Salomon’s notes make it clear why:

What would make my parents–any parents–want to send their little children, in our case five-year-olds, to live with strangers in another country? Another country with which one’s own country might soon be at war? Indeed my father was a decorated veteran of Germany’s First World War army; he must have understood that his service record might mean little or nothing. The cosmic wind had changed direction.

…

Somehow my parents decided in 1938 or 1939 to try to send their children out of the country for which my father had fought… Neither they nor anyone else–no German–could have foreseen the ugliest forms that the future would take… or were there incidents where threats or calls to kill children, as had happened to grandmother and us on the bridge over the Dill, had been carried out?

Since his release from the Buchenwald concentration camp – and certainly as a condition of release – Julius Salomon also tried to emigrate his family. The sale of his house, his plots of land in Werdorf, and – eventually – most of his home furnishings are related to this. From a letter to the foreign exchange office “S” dated July 20, 1939, it becomes clear that he was trying to allow emigration for himself and his family:

… At the same time I ask you to allow me to temporarily release 5,000 RM from the above amount, for living expenses and for preparing the emigration for my family.